Stellako Select

We are the Stellat’en fisheries, practicing both modern and traditional fisheries of the Carrier First Nations on the Endako, Stellako, Nautley, and Necho Rivers and Fraser Lake.

While our network of local lakes and rivers support healthy and abundant resident fish stocks, we also enjoy chinook salmon and even strong cycle returns of sockeye that can support local subsistence, commercial and sport fisheries on good years.

Fishing for salmon we use dip nets and gaff to selectively harvest returning salmon from our river fences and traps that are based upon traditional designs. Our traditional fish fence is a symbol of our fisheries because it was once outlawed, as it was once thought to be the cause of salmon declines until scientists and managers learned about the long journey and many fisheries our salmon went through before returning back home to spawn.

In recent years our river trap has been used primarily for scientific and subsistence purposes, and our commercial harvest of sockeye is conducted in Fraser Lake using a purse seine to harvest the available surplus during high cycle returns.

Location & Significant Feature

Only 11.3 kilometers long, the Stellako River drains the fertile land between Francois Lake and Fraser Lake just west of Fort Fraser and in the traditional territory of the Stellat’en First Nation in the Omineca Country of the Central Interior of British Columbia. The Stellat’en First Nation is the band government of the Stellat’en subgroup of the Dakelhne or Carrier people

At the center of their territory, the Stellako River merges with the Endako River before flowing into Fraser Lake, which drains into the Nechako River via the Nautley River. The Nechako River joins the Fraser River some 160 kilometers to the east at Prince George. Once the basin of a glacial Lake and home to at least one extinct volcano, the surrounding plateau is dotted with countless lakes and rivers on the cusp of mountain ranges dividing the Skeena watershed to the north-west and the Fraser watershed to the south-east.

Stellako sockeye travel nearly 900 kilometers from the ocean up the Fraser River to get here. These sockeye are among the farthest inland traveling sockeye populations in the Pacific. An important component of the Fraser’s summer-timed sockeye populations, the returns, often numbering in the hundreds of thousands, seek out the productive glacial gravels and clean abundant flows found in the spawning grounds of the Stellako River, as well as local tributaries including the Nithi River and Ormond Creek.

Each year these sockeye support the needs of local traditional fisheries as well as fisheries occurring in marine approach areas and throughout the Fraser River. When returns are strong a selective commercial purse seine fishery occurs in Fraser Lake . Stellat’en’s strategic location, cross-cut with uncountable trails connecting the coast and interior tribes, was once the center of busy trade system. Highly dependent upon the area’s sockeye populations, Stellat’en are the traditional stewards of these “Stellako sockeye” and active co-managers with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) and the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council.

Mission

Stellat’en strives for a holistic approach to managing migratory salmon with abundant resident fish species as part of preserving this ecosystem for generations to come. Our objectives include:

- Increase community responsibility for watershed management;

- Increase local watershed surveillance and monitoring;

- Increase the number of qualified fisheries technicians within the delivery area;

- Increase stakeholder and public awareness of fish and fish habitat requirements;

- Increase fisheries projects within the core territory of Stellat’en First Nation

- Encourage youth to seek further education and training that will increase their employability in the natural resource sector.

- Identify individual needs of participants such as education level, training, work experience and career planning.

Traditions

Stellat’en is strategically located on the shores of Fraser Lake at the confluence of the Stellako River.. Providing both navigation and access to a lucrative salmon fishery, management of the areas fishery resources has always been critical to critical to Stellat’en’s culture.

History

From Stellat’en First Nation Website – for more information: http://www.stellaten.ca/About/BandHistory/Pre-ContactStellaquo.aspx .

“In pre-contact era there was a natural cycle of life. The yearly flood plains would come and go with the weather patterns. The winters were harsh. The wildlife was in abundance. There was no mystery to living healthy and surviving it was just done according to the laws of our ancestors…”

Modern Fishery

Around the turn of the last century, the growing Canadian Pacific salmon fishing industry thought there was no end to the boundless productivity of Pacific salmon. The growing fleet would not face significant restrictions for several decades to come, but the scarcity of sockeye in some years and ongoing competition from Indians selling to the Hudson’s Bay Company led to predictable finger-pointing.

Government intervention on behalf of the canneries was to be the harbinger of economic hardship for the Stellat’en that would last more than 100 years. To blame, it was said, were the Indian fisheries on several major sockeye rivers in BC including the Stellako and the Stellat’en fishing weir, a fishing technique referred to by the industry as “barricading”. Stellatin weir photo from Nadleh Nautley River.

In 1904, responding to pressure from the canneries, the government of Canada decided to ban traditional fishing weirs and introduced the “Barricade Agreements” or fishing treaties, first to the Skeena, and then in 1911, to the upper Fraser River. These treaties outlawed the weirs and in return made extensive promises ranging from fishing nets and education to farm implements, and in some cases additional reserve land. In addition, the treaties outlawed the sale of salmon by the Indians. Two formal agreements were signed in Fort Fraser. Chief Isidore, of Stella, is recorded signing a Barricade Treaty on June 15, 1911.

The terms of the Barricade Agreements were never fully honored by the Crown, and remain a significant matter of contention with many inland First Nations, including Stellat’en.

In 1994 Stellat’en engaged in the Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy (AFS) via the Carrier Sekani Tribal Council (CSTC). The AFS has supported Stellat’en’s engagement in stock assessment activities.

Stellat’en members, CSTC staff, and DFO staff work together to enumerate sockeye salmon spawners returning to the Stellako River. In recent years, returns have been assessed utilizing DIDSON (acoustic) technology.

Sockeye spawners are also enumerated through visual counts by floating the Stellako River at which time sampling, mark/recapture, and dead pitches are completed.

In 2014 Stellat’en experimented with the first modern commercial fishery of its kind in the area.

Local salmon conservation Issues

Stellat’en have a concern for all fish species, not just the sockeye or chinook salmon. Other important species include Rainbow Trout, Bull Trout, Whitefish, Kokanee, Burbot, White Sturgeon, and non-game species. We have concerns about short-term resource exploitation at the long-term expense of our environment.

The Endako River chinook population is severely depressed, and an early timed run of sockeye to the Nadina river is trending within a diminished status. While watershed environments are the constant focus of our stewardship, our greatest concern for wild Pacific salmon is directed at mixed-stock salmon fisheries that over-fish less productive stocks in their quest for the abundant ones. We promote local stock-selective fishing in areas where we know that the stronger stocks can be selectively harvested out of the path of weaker ones – sometimes this means fishing in the tributaries or at times when and with gear that cannot harm the weaker or less productive stocks.

This is our traditional knowledge and experience, and we hope by sharing our story with others we will bring about change before less productive stocks are fished out of existence.

Stellako River – the end of log drives in British Columbia

In the 1960’s the Stellako became the epicenter of an inter-jurisdictional controversy in BC surrounding the now outdated logging practices of log drives.

The technique involved dropping fresh logs into a headwater lake blocked by a removable log dam. When released the flush of water and logs saved money in log transport but left behind its devastating effects on fish habitats.

With many parallels around BC including the Quesnel, Adams, and Kitsumkalum Rivers, it was the local economies around Fraser Lake that pitted the Provincial government against the Federal government. The Stellat’en found themselves unwilling bystanders in the fight between unsustainable logging practices and a coastal industrial fishery, neither of which would survive in their current form beyond the next century. The sockeye runs were greatly diminished before log drives were outlawed in 1973, and a sockeye spawning channel was eventually constructed on the Nadina River in an effort to boost Francois Lake’s sockeye to help revive the run.

is fishery produces on average 0.5 – 1 million lbs of salmon (sockeye, chum, pink, coho, and Chinook). Harvesting occurs through a variety of methods, locations, and times (to ensure selectivity), and operates through a membership of more than 200 designated Community fishers. The cooperative landing site and incentives for entrepreneurial growth recruit the fishers into finding solutions around responsible fishing practices (including effective governance), improved prosperity for fishers (value-adding), and catch accounting (including traceability).

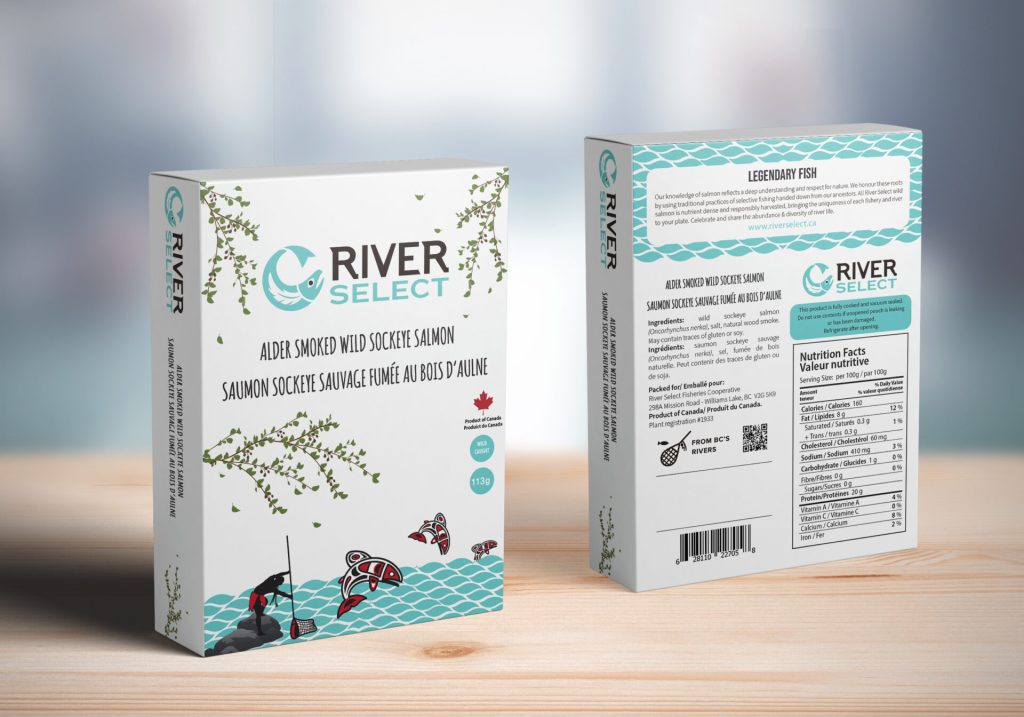

About Our Logo

The Stellako Select Logo was designed in celebration of the traditional fish weirs as a monument to the resilience of the Stellat’en People and their unwavering commitment to the conservation and sustainable use of Stellako sockeye and the stewardship of local watersheds that these salmon call home.

Links

- Stellat’en Website: www.stellaten.ca

- Carrier-Sekani Tribal Council Website – Fisheries co-management: http://www.carriersekani.ca/programs-projects/natural-resource-stewardship/fisheries1/

- Barricade Treaties – Lake Babine First Nation website: http://www.lbntreaty.com/history-culture/timeline/the-barricades-are-protected-and-the-treaty-is-made-1906/